Apps, says Gartner, are not applications: “The defining characteristic of an app is its reduced functional presence. Apps do less than applications. That is their goal.”1 In other words, what began as mere shorthand for most of us (“The $#!@% app is down again!”) has come to represent a different design paradigm altogether.

How do we separate the usage of the terms? The distinction is driven primarily by the device. Big screen, full keyboard, unlimited power, etc.? That’s the playground for applications. Small touch screen, small keyboard, limited battery, limited bandwidth? That’s where apps thrive.

While some folks may quibble with this distinction (“But my Mac runs apps too!”), this kind of hair-splitting doesn’t really take us anywhere useful. It is the “artificial constraint” of mobile device form factors that has given rise to the creative simplicity of apps.

Understandably, for many companies the app/application difference remains hidden or misunderstood. Shedding our legacy thinking about what an application is for, or what makes one good, isn’t easy. But it’s central to any winning mobile strategy. Why? Because grasping the distinction affects not just how we design the user interface, but how we architect and what we need from our software infrastructure. It’s these cumulative differences that inform what users have come to expect from the mobile experience.

What’s in a Name?

In our e-booklet on the three keys to becoming a mobile enterprise, we described the difference this way:

Applications are baggy monsters prized for their long lists of capabilities, while apps are valued for doing a few things well — their purposefulness.

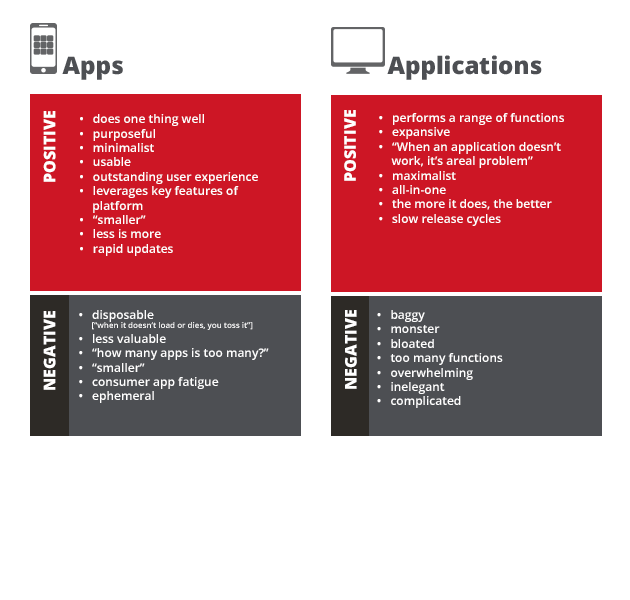

As it happens, plenty of folks (not just Gartner) see this too. A scan of first-page Google results contrasting “apps” and “applications” yields some other interesting distinctions:

Of course, we need both. Apps help us move faster, and to accomplish things anytime, anywhere; applications drive complex tasks as well as those demanding heavy data input. The trick is to recognize the difference, and be explicit in your purpose.

How the Biggest Applications Are Becoming Apps

Although there will always be a place for applications, it seems fair to say people much prefer the app experience. Having a context-aware bit of software that, in a matter of a few swipes of the finger, can accomplish what you need is a powerful draw. How else to explain mobile’s explosive popularity? (It sure isn’t the voice quality.) And even the biggest of big applications are going that way.

Take Facebook, an enormous web application whose codebase is nearly as big as that of the Windows OS. But despite its massive popularity, CEO Mark Zuckerberg recently explained that the company’s chief strategy amounts to “basically unbundling” the application and creating a series of targeted mobile apps. Why? Because mobile is where the growth is. And as Zuckerberg puts it, “In mobile, there’s a big premium on creating single-purpose, first-class experiences.”

Other consumer players like FourSquare are following suit, and some feel Twitter would benefit by taking a harder look at the purposefulness of its current app offering. This has implications for enterprises as well. We often encounter companies early in their mobile maturity. In many instances, the impulse is to mobilize their work forces via a single, “super app” – one program that rolls together everything an employee might want (benefits, expense management, conference room reservation, and so on).

It’s an understandable impulse. These companies worry that with the rise of mobile, they’ll exchange the old feature-bloat problems of their applications for “app-store bloat”. But it’s a reflection of legacy application thinking. It’s the very targeted purposefulness of apps that drives usage and adoption. A “super app” goes in the opposite direction, working against what these companies want to achieve – namely, an engaged, empowered mobile workforce. It also ignores the fact that app stores are by nature Darwinian places: the strong survive, the weak are ignored and deleted. This is a stark difference from the old application days, when any one person’s favorite feature became something that everyone had to live with.

It’s Bigger Than Merely “Smaller”

Apps are smaller than applications, yes, but that’s hardly the sum total of their difference. In fact, the way we design, build, connect and optimize apps is new:

- Fewer features means faster cycles – the bite-size nature of apps naturally lends itself to iterating and improving much faster than we ever could when changing a monolithic application. It also means smaller teams with fewer handoffs, less overhead, and better collaboration.

- Context heightens engagement – the 24/7 attachment to our mobile devices, their awareness of factors like location, and new capabilities such as push allow us to rethink our business processes and provide meaningful interactions in a way the blind, desk-bound PC application never could.

- Fast, modern architectures – because of the constraints of legacy web architectures, mobile encourages (requires?) companies to establish an API strategy for fast, simple access to data. This means developers and partners (and even 3rd parties) will sink less time into tedious integrations and can instead focus on innovation and great user experiences.

- Data-driven decisions – the rise of analytics capabilities that can be auto-deployed into our apps means we no longer have to make decisions based on guesswork and gut-feel. We now have real-time information on app behavior, user sentiment, and business goals. This upends the traditional notion of “requirements gathering” and tells us with precision exactly what should go into the next release.

Together, all of this means that we can be much more responsive to our users. So while it’s important to be thoughtful with your words — apps vs. applications — it’s even more important to understand the real differences and how “app thinking” can challenge the decades of conditioning we’ve had on how we should build software. Your users will thank you for knowing the difference.

1 Prentice, Brian. “The App and Its Impact on Software Design.” Gartner. 18 May 2012.